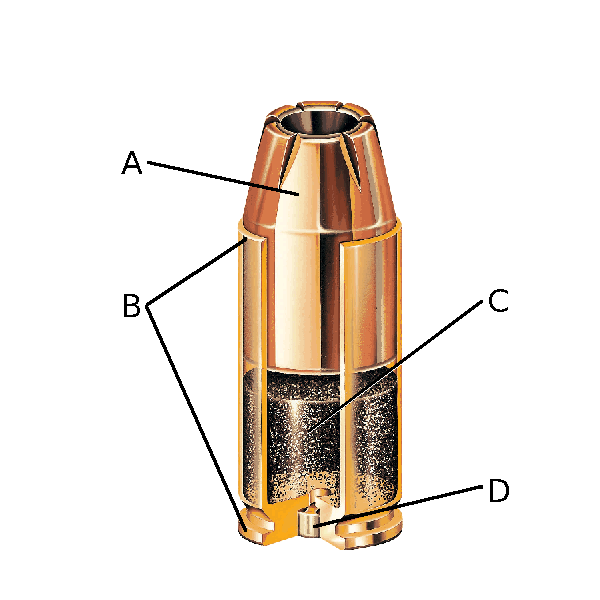

| |

| Proper Name | Slang Name |

| A: Projectile (bullet) | Bullet |

| B: Cartridge Case | Shell |

| C: Propellent or Powder | Gun powder |

| D: Primer | Cap |

Modern ammunition consists of four components:

What people commonly call "bullets" are really an assembly of propellant, projectile, and primer, held together by a cartridge case. The entire assembly is called a "cartridge".

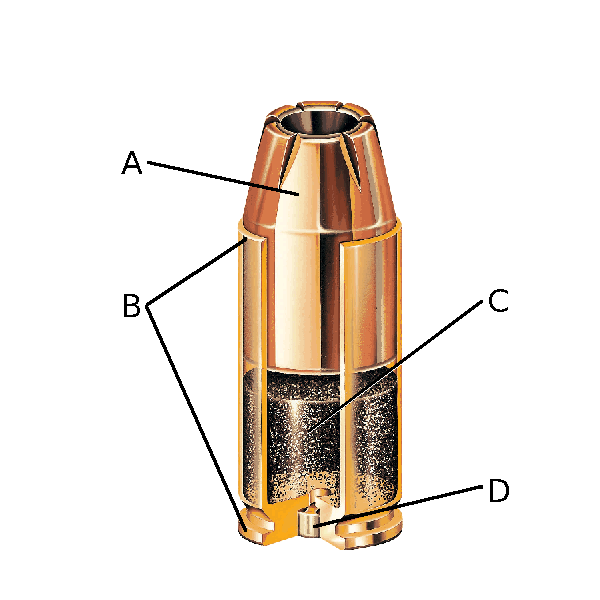

| |

| Proper Name | Slang Name |

| A: Projectile (bullet) | Bullet |

| B: Cartridge Case | Shell |

| C: Propellent or Powder | Gun powder |

| D: Primer | Cap |

The projectile is the component that does the work required of a firearm. Generally, a bullet is a single projectile fired from the barrel of a firearm and is part of the gas seal system. Just as the rear of the gun barrel must be sealed, the bullet forms a temporary seal at the opposite end of the cartridge case (obturation), allowing gas pressure to build to levels required for good combustion and velocity.

The earliest cannon projectiles were ball-shaped stones rounded to fit a crude cannon bore. As metal-casting technology improved, balls were cast of common metals, such as iron. Casting allowed for a more precise shape and uniformity of size and weight.

When small arms evolved, everything had to be scaled down for portability. Small, round balls of stone or iron are no longer used, but the term "round" (plural: "rounds") is still in use. A cartridge (consisting of a projectile, propellent, powder and case) can properly be called a "round". Confusingly, when you "fire some rounds at a target", the inference is that only the projectiles (the bullets) went downrange.

Firearms work by first igniting the propellent, or gun powder. When the powder starts to burn, it produces hot gas which expands very quickly. This burning of the propellent is initiated when the weapon's firing pin hits the cartridge's primer. The primer creates a tiny flash of combustion that ignites the powder inside the cartridge case.

The expanding gas is contained inside the cartridge case, which is, in turn, held in the weapon's firing chamber. The chamber is made of very strong steel and holds back the pressure of the expanding, burning, powder. The easiest direction for the expanding gas pressure to go is out of the mouth of the cartridge case, pushing the bullet out ahead of it.

The bullet is forced out of the cartridge case and firing chamber, into the barrel of the weapon at very high speed (velocity). As long as there is powder that is still burning, the projectile continues to accelerate, as the pressure of the expanding gas is still contained by the cartridge case (that is inside the chamber) and the strong steel barrel of the weapon.

Inside of the barrel there are helical grooves. These grooves are called "rifling" (even in a handgun, they are called "rifling", not "pistoling"!). The metal that the bullet is made from is softer than the steel that barrel is made from and the bullet actually is "hammered" into the grooves upon firing.

These spirally arranged grooves impart a "twist" movement to the bullet as it travels down the barrel. When the bullet exits the barrel it is spinning in a perfectly spiral motion, just like football quarterbacks attempt to do when making a pass. This is called "spin-stabilization" and is the same thing you see when a child is playing with a top or dreidel.

All of this takes place in a fraction of a second! As soon as the bullet leaves the muzzle of the barrel the pressure drops almost instantly. Any excess, unburned powder will be burned outside of the barrel, producing what is called "muzzle flash", and the bullet is now flying down range, stabilized by the spinning motion imparted to it by the rifling in the barrel.

Meanwhile, back in the firing chamber, the relatively "stretchy" brass metal that the cartridge case is made from has expanded to match the size of the chamber for just a moment. It then springs back to slightly larger than the original size. If you were to eject the empty cartridge case right away, you would find that it is very hot!

Ejected cartridge cases from high-powered pistols and rifles are a bit of a safety hazard. Not from the actual burn wound they might cause, but from the fact that the impact and heat may startle you and cause you to "do a little dance" on the firing line, with a loaded gun in your hand!

For this reason, when you participate in an Our Safe Home Clinic you need to wear a "crew neck" or "turtle neck" type shirt (and not a "v-neck", ladies!). You do not want a hot cartridge case to be caught by your collar and go down the front of your shirt. Ouch!

"Stopping power" is the colloquial term used to describe the ability of a firearm or other weapon to cause a penetrating ballistic injury to a target human or animal, an injury sufficient to incapacitate the target where it stands.

The term refers only to a weapon's ability to incapacitate quickly, regardless of whether death ultimately results. It is not a euphemism for lethality. Some theories of stopping power involve concepts such as "energy transfer" and "hydrostatic shock". Among the self-defense community there is strident disagreement regarding the importance (or even existence!) of these effects.

Stopping power is related to the physical properties of the bullet and the effects it has on its target, but the issue is complicated and not easily studied. A given weapon cartridge combination may produce a "One Shot Stop" value of 75%. That is to say that 75% of the time that an attacker was shot with this combination, the attacker was immediately incapacitated. (By implication, 25% of the time more than one shot was necessary!) Many people feel that the importance of "one-shot stop" statistics is overstated, pointing out that most self-defense encounters do not involve a "shoot once and see how the target reacts" situation.

"The Stop" is rarely by the force of the bullet (particularly in the case of handguns), but by the damaging effects of the bullet which are typically a loss of blood, and with it, blood pressure. More immediate effects can result when a bullet damages the central nervous system such as the spine or brain. Techniques like the "double tap" have been developed, to maximize the likelihood of a quick incapacitation of an attacker when using pistols or revolvers.

The concept of "stopping power" appeared in the late 19th Century when colonial troops (American in the Philippines, British in New Zealand) engaging in close action with indigenous warriors found that their pistols were not able to stop charging warriors. This led to more powerful handguns being developed to theoretically stop opponents with a single shot. The term "Manstopper" is now used to describe almost a combination of handgun and ammunition that can reliably be expected to incapacitate, or "stop" a human target immediately.

A bullet will destroy or damage any tissues which it penetrates, creating a wound channel. It will also cause nearby tissue to stretch and expand as it passes through tissue. These two effects are typically referred to as permanent cavitation (the hole left by the bullet) and temporary cavitation (the tissue displaced as the bullet passed).

The degree to which permanent and temporary cavitation occur is dependent on the weight, diameter, material, design and velocity of the bullet. This is because bullets crush tissue, as opposed to cutting like a knife would.

For the most part, there are two general categories of bullets to consider: expanding and non-expanding. A non-expanding bullet will crush only the tissue directly in front of the bullet, causing a deep and narrow wound channel.

The non-expanding bullet may exit the target and continue its flight with enough energy to hit, damage or destroy something else it encounters.

A bullet that expands upon impact will crush tissue in front and to the sides as the bullet passes through the target. The hollow-point hand gun bullet is conducive to causing more permanent cavitation as the tissue is crushed and accelerated into other tissues by the bullet, causing a shorter and more voluminous wound channel.

Due to the energy expended in bullet expansion, velocity (and therefore energy) is lost more quickly than a non-expanding one.

The copper covering of a lead bullet is called the jacket. If no lead is visible on the outside of the cartridge, the bullet has a Full Metal Jacket (FMJ). Handgun ammunition that incorporates a Full Metal Jacket usually incorporates a Round Nose (RN).

FMJ ammunition is specified for military use by the countries that signed the Hague Convention of 1899, which prohibits the use of hollow-point or expanding bullets in war between the countries which signed that agreement. It is often incorrectly stated that the prohibition is part of the "Geneva Conventions". It is also a common misconception that full metal jacket bullets are specifically required by the Hague Convention; they are not.

Round nosed Full Metal Jacketed bullets do not expand, they are more effective at piercing armor or any other type of shielding material (car doors, interior walls, etc.). They are more durable and withstand rough handling on the battlefield. Their rounded tips permit proper transit up the feed ramp, whereas the usage of hollow point bullets can cause failures to feed in an autoloading pistol. By way of contrast, revolvers have no such feeding difficulties at all.

Because Round nosed Full Metal Jacket (RN-FMJ is an abbreviation you may see) bullets do not expand, they are less likely to stop an attacker immediately compared to hollow-point bullets. At close range because the bullet may go straight through the attacker, wounding them, but not stopping them instantly. Hunters are, in some locations, not allowed to use FMJ rounds due to their limited stopping power and greater likely to over-penetrate and/or ricochet.

|

|

Two bullets were fired at this block of ballistic gelatin. The upper track was made by a hollow point self-defense type bullet that penetrated an ideal 14.5 inches and expanded to a respectable 150% of its original diameter. The lower track was made by military-type Full Metal Jacket bullet that passed through 16 inches of gelatin, exited and continued down range. It did not expand at all, clearly demonstrating minimal energy transfer and over-penetration! See the details here.

|

Round nosed bullets are shaped just like full metal jacketed bullets, but the are manufactured with out the metal jacket. They combine the "non-expanding" feature of the FMJ bullet, but are unable to penetrate shielding material as well as jacketed bullets. Why would anybody want them? Because they are much less expensive!

In conclusion, Full Metal Jacketed (FMJ) and round nosed (RN) bullets are the least desirable types of bullets for self-defense purposes, and are best used only for target practice, thanks to their economy.

Hollow-point bullets are one of the most common types of civilian and police ammunition, due largely to the reduced risk of bystanders being hit by over-penetrating or ricocheted bullets, and the increased speed of incapacitation.

A hollow point is a bullet that has a pit or hollowed out shape in its tip, generally intended to cause the bullet to expand upon entering a target in order to decrease penetration and disrupt more tissue as it travels through the target. In rifles, hollow-point bullets can offer improved accuracy by shifting the center of gravity of the bullet rearwards. Jacketed hollow points (JHPs) or plated hollow points are covered in a coating of harder metal to increase bullet strength and to prevent fouling the barrel with lead stripped from the bullet.

When a hollow-point hunting bullet strikes a soft target the pressure created in the pit forces the material (usually lead) around the inside edge to expand outwards, increasing the axial diameter of the projectile as it passes through. This process is commonly referred to as mushrooming, because the resulting shape, a widened, rounded nose on top of a cylindrical base, typically resembles a mushroom.

The greater frontal surface area of the expanded bullet limits its depth of penetration into the target, and causes more extensive tissue damage along the wound path. Many hollow-point bullets, especially those intended for use at high velocity in centerfire rifles, are jacketed, i.e. a portion of the lead-cored bullet is wrapped in a thin layer of copper. This jacket provides additional strength to the bullet, and can help prevent it from leaving deposits of lead inside the bore. In controlled expansion bullets, the jacket and other internal design characteristics help to prevent the bullet from breaking apart, a fragmented bullet will not penetrate as far.

The hollow-point bullet, and the soft-nosed bullet, are sometimes also referred to as the dum-dum, so named after the British arsenal at Dum Dum, India, where it is said that jacketed, expanding bullets were first developed. This term is rare among shooters, but can still be found in use, usually in the news media and sensational popular fiction. The term "Dum Dum Bullet" refers only to soft point bullets, not to hollow points, though it is very common for it to be mistakenly used this way.

One of the most interesting philosophies to come out of the last 40 years of the police and citizens using hollow point ammunition is that hollow points actually cause fewer fatalities than Full Metal Jacket ammunition. This reasoning behind this seemingly counter-intuitave observation is that criminals have to be hit fewer times with hollow point bullets than with FMJ bullets to bring about incapacitation (ie: two shots rather than six to achieve a "stop"). The (incapacitated, but still alive) bad guy is delivered to the emergency room with two gunshot wounds rather than six and the medical staff can treat all of his wounds in one third of the time.

While this cannot be counted upon in each and every situation, the effects of widespread use of hollow point handgun ammunition are undeniable: More "stops" of attacks, and fewer dead attackers. The real benefit is not, however, to the attacker, rather it is to the defender, who does not have to carry the burden of having taken a life. Virtually everyone who has been forced to kill in self-defense says that they wished the attack could possibly have ended without the death of the attacker.

While the relative effectiveness of different types of handguns and bullets has been debated for two centuries, there are a few undeniable truths:

From these principles, experts have observed the following particulars:

Handguns that are more powerful than the 9mm (.357 Magnum ,.41 Magnum, .44 Magnum, etc.) may achieve slightly better "one-shot-stop" statistics, but are much harder for the occasional user to shoot accurately. A miss with a more powerful gun will not stop an attacker!

No handgun has ever demonstrated a "one-shot-stop" rate of 100%, therefore, if you are attempting to stop an attack you will have to hit the attacker at least twice! These hits are best placed in the center of the attackers chest area, with the hope that an incapacitating blow will stop the attack.

The reasons for attempting to hit our attacker in the chest are many:

At this stage of you training (even if your training goes no further than attending an Our Safe Home Clinic), aiming for two "Center Mass Hits" on an assailant yields the highest probability stopping the attack in a timely manner.